Back in 2019, the poet and teacher Kate Clancy put together a book on her experiences working with migrant children in the UK:

Jay Doubleyou: poetry in the classroom: some kids i taught and what they taught me

The book was very well received at the time:

“Hide the fact / You are alienated” commands Priya, a schoolgirl poet taught by Kate Clanchy, who considers her life as a migrant. “Chew on the candy floss. / It melts in your mouth. Such foreign stuff!” The poets Clanchy has nurtured at the comprehensive where she teaches in Oxford are now well known. They’ve won poetry competitions and been included in her anthology England: Poems from a School. In Some Kids I Taught Clanchy has set out to tell the story of how this happened, while analysing the wider educational landscape in Britain over the past 20 years.She was awarded the prestigious Orwell Prize:

"In this book, a brilliantly honest writer tackles a subject that ties so many people up in knots – education and how it is inexorably dominated by class. Yet this is the very opposite of a worthy lecture: Clanchy’s reflections on teaching and the stories of her students are moving, funny, full of love and offer sparkling insights into modern British society.”Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me | The Orwell Foundation

And she talks about her time with students during the pandemic - on her publisher's website:

However, late last year, some readers started to attack the book and the writer:

Cancelling Kate Clanchy won't root out real racism - New Statesman

Here's a critic

Should the book be rewritten? Not in my view. The damage is done and the harm is caused; you can’t put that bunny back in the box. Worse, allowing Clanchy to re-write it gives legitimacy to the idea that she was in some way subjected to ‘cancel culture’. And finally, rewriting it means the problem is pushed under the rug along with the old editions.

If you’d like to read work by some of the authors mentioned in this piece who don’t utilise racist and ableist tropes, try out Dara McAnulty’s fantastic Diary of a Young Naturalist and the new middle grade Wild Child (the illustrations in this are honestly some of the best I’ve ever seen). Monisha Rajesh’s Around India in 80 Trains is an excellent glimpse inside her family history and the lifeline of the railways — and Chimene Suleyman’s work on The Good Immigrant USA means it’s a must-read.

What’s clear is that publishing has a long road ahead — and after this, I’m not sure it’s ready to face the journey, for all its platitudes about diversity after #PublishingPaidMe.

Lessons to Learn From the Kate Clanchy Memoir Fiasco

And here is a supporter:

Clanchy is not without support. One former student, Shukria Rezai, wrote an impassioned defence of her teacher in The Times, describing Clanchy as someone who had “fought” for and given “platforms” to her students. Rezai, the student who Clanchy had described as having “almond eyes'', stated that she did not find the term offensive. Indeed, she went on to describe how the term was a “beautiful reference” in Hazara culture and reminded her readership of how the Taliban persecuted her people; she expressed gratitude to Clanchy for making the Hazara people “visible”.

It’s concerning that institutions like the Royal Society of Authors and Picador failed to stand up for Clanchy’s right to freedom of expression and, instead, bent a knee to the will of the Twitter mob. Clanchy’s rewriting brings to mind the image of Winston Smith rewriting documents in the Ministry of Truth—truly Orwellian. And most importantly, that Kate Clanchy, an educator who has spent thirty years working in the state system with predominantly disadvantaged students, has had her reputation torpedoed, becoming the latest persona non grata in the culture wars, is troubling.

How on earth could a book released to widespread critical acclaim just over a year ago cause such widespread outrage now? That was the question I sought to answer when I decided to read the book for myself, form my judgement, and put my reflections down on paper.

Let me say from the outset that I think Clanchy’s critics are wrong to accuse her of racist language.I took no offence in Clanchy’s descriptions. It simply is not considered a racial insult by the person who Clanchy was describing. “Chocolate-coloured skin” while clumsy prose is hardly offensive (for the record, I have chocolate-coloured skin). “African Jonathan'' is a strange way to describe someone, but again, not offensive. The other racial descriptors were, to my mind, just that, short sketches of the person being described whether they were Somalian, Afghani, or Pakistani.

...

All in all, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me is a book that professes a sincere love of the profession, of students, and of schools themselves. Kate Clanchy has been treated terribly, particularly on social media, and has been the victim of an attempt to tarnish her work and her reputation. Much of what is circulating on social media has been taken out of context. She is yet another leftwing figure attacked by other, more extreme, leftwingers. I hope she continues to write about teaching and I hope that publishing houses continue to publish her work. Rather than relying on reading excerpts collated online to make the book and its author appear in the worst possible light, I would urge you to read it for yourself and form your own judgement.

It's just been republished:

Kate Clanchy’s controversial memoir reissued by independent publisher | Kate Clanchy | The Guardian

Some Kids I Taught & What They Taught Me: 9781509840298: Amazon.com: Books

Finally, the publisher that has unpublished her still has articles written by her on their website:

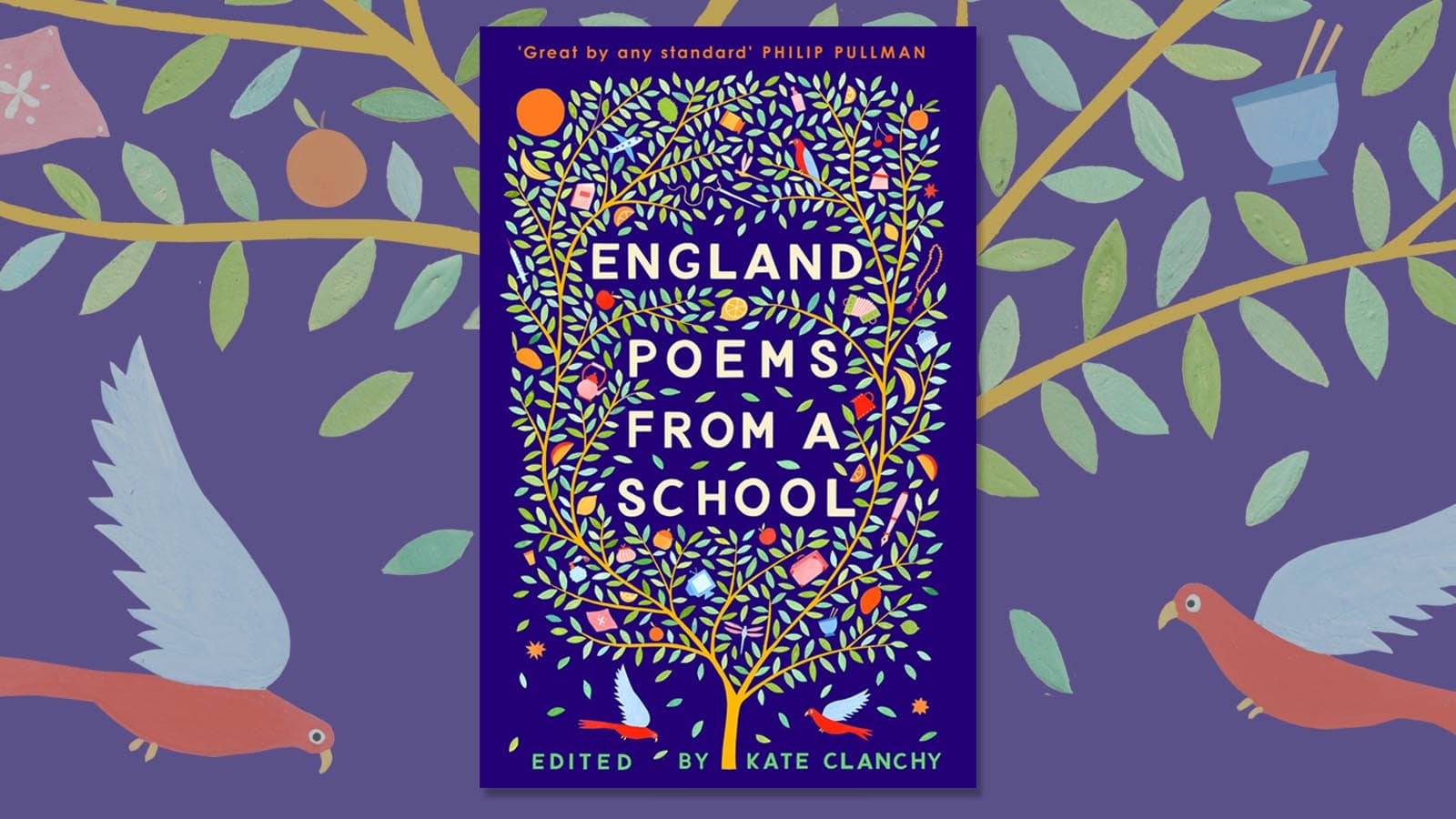

Introducing: England: Poems from a SchoolPicador poet and English teacher Kate Clanchy introduces some of the poets who feature in new anthology, England: Poems from a School.

Picador Poet Kate Clanchy shares the story behind new poetry anthology, England: Poems from a School, and introduces some of the poets whose work features in the collection. England is published in paperback and ebook on 14th June 2018.

For the past 9 years I've been working as Writer in Residence at my local comprehensive school, Oxford Spires Academy. It's the chosen school of Oxford's many migrants: more than 30 languages are spoken here, our students come from all over the world, and everyone, including the white British students, is a minority. That makes for a very special, open culture, and a very creative one too: our students paint, dance, act, and sing with enthusiasm, all the time. And they write: in fact, in the last five years, we've become the UK's most successful poetry school, winning all the competitions for young people multiple times, creating a Ted Hughes Award nominated radio programme, and, most recently, enchanting Twitter and winning thousands of followers with their direct, moving verse.

England: Poems from a School brings together our very best poems in one anthology to create a rich portrait of England as it is experienced by its youngest migrants. The result is very likely to make you cry - but not just because of the sadness of some of the stories. There is an openness here, a warmth, a reality which speaks directly to the human heart. These are also poems to share and show: to young people and old, migrants and their neighbours. The poems document migration, which a central experience of our contemporary world, but they also remind us of the ancient purpose of poetry; to share, to explain, and to remember.

Home byMohamed Assaf (12)

I miss being in the land

where I was born and grew up.

Our dreams are there

but my destiny is not to be

with Damascus who gave me my soul.

Damascus where the sun rises in my room

and the birds sing at my window.

Damascus, my mother.

Mohamed wrote this very moving poem in Arabic in a workshop with the Iraqi poet Adnan Al- Sayegh just a few months after he arrived in our school from Syria, and it was translated with help from @CreativeMultilingual. Mohamed has written many poems since and is a huge star on twitter. He also likes basketball.

From Origins, byAzfa Awad (18)

I grew up here:

resting under the palm trees

drinking Dafu juice,

snoozing on the Baraza beneath the stars.

I grew up here: in the Gorbals,

with Kwiksave, the Junkies,

and chucking snowballs;

watching fireworks

on the eighth floor of my council flat,

listening to the bangs and cracks;

watching the orange flames

flower out.

This is part of the stunning poem about her Tanzanian origins and Scottish childhood that won Azfa Awad the Tower Poetry Prize in 2013. She's since gone on to university, and to launch her own poetic career. Azfaawad.com

A poem by Amineh Abou Kerech(13)

Can anyone teach me

how to make a homeland?

Heartfelt thanks if you can,

heartiest thanks,

from the house-sparrows,

the apple-trees of Syria,

and yours very sincerely.

Amineh and her sister Ftoun are refugees from Damascus. They write poetry together, helping each other to understand their journey from their beloved home. This poem was part of a long one, translated from the Arabic, which won Amineh the John Betjeman Prize.

A poem by Shukria Rezaei (18)

I want a poem

that sits on a silver plate with

nuts and chocolates, served up to guests who

sit cross legged on the thoshak.

A poem

as vibrant as our saffron tea

served up at Eid.

Let your poetry

texture the blank paper

like a prism splitting light

Don't leave without seeing all the colours.

Shukria arrived in our school when she was just 14: traumatized by the conflict she had witnessed in Afghanistan but very determined. She wrote poetry almost before she had the English words to do so. This poem, like so much of her work, reflects her love for her Hazara culture.

From War Memoir by Azfa Awad (17)

I may have been small

but when trapped

between the claws of war

my voice could soar:

sound like the bangs and cracks

spat by the tongues of fireworks;

And when I ran

away from their biting guns,

my feet could dance,

skim above rose petals

dripping from my toes.

Azfa Awad remembers the trauma that forced to migrate to the UK. Her rich rhymes and sensual, unsentimental memory of exactly what it felt like to be a child marks her out as a poet. Azfaawad.com

From When I came from Nepal by Mukahang Limbu (15)

I did not know,

of silence in the streets,

or the secret whispers on the buses,

or the sly gestures of restaurants.

In this place,

where I did not know,

the things I did not know

embrace me in ways

I didn't know.

This is part of the poem which won Mukahang the First Story National Writing Competition when he was just 13. It reflects his Nepalese origins and his perceptive, yet very positive, feelings about his move to England when he was five. Mukahang is interested in theatre and languages as well as writing and we all expect him to be famous.

Hungary by Vivien Urban (14)

Look,

these flat lands

before you. Endless sky

fills empty space.

Stand here,

and open up your mind.

Notice the light

riding on its cloud horse

throwing shadows

on the grassy ground.

Stand here

and hear the whistle of the wind

blowing the golden sand.

Remember it,

elsewhere,

the free and wild wind,

as a gentle touch.

Vivien had been in England for less than three years when she wrote this beautiful poem about her homeland in response to Auden. She went to be our Head Girl, get stellar A Levels and win a place at St Andrew's University.

My Poem is a Jackfruit by Emee Begum (16)

The smell of it clings.

And the inside feels

like the gooey ink

that my brother puts

in his red car engine.

It is tough as wood,

scaly as a dinosaur.

But inside, soft as wool.

and the taste is

sweet heavens,

the world's greatest foods

having a party.

Emee's poems have a very special childlike vision, and often remember her Bangladeshi childhood. Jackfruit are the huge rugby-ball shaped fruit with a soft centre which sometimes appear on UK street corners, but in Bangladesh are the national fruit.

Sylhet by Rukiya Khatun (16)

There,

Sun birds chipper,

Their feathers, light lime,

Seep in the sunshine.

Mango trees

Summit and soar,

Stalk high above

The forest floor.

Where

A Bengal tiger,

Obsolete

As an emperor

Trembles

As the hushed wind-

Breathes –

Rukiya's poems were always about her childhood in Bangladesh and her journey to England when she was six. This poem shows a child's vision of a jungle and has a gorgeous soundscape.

Homesick by Shukria Rezaei (18)

Today, I thought of my mud house:

The rough walls standing tall;

The fresh smell of clay on the floor;

The scraping of dirt from my shoes.

Today I missed the jagged roads.

The horizons of mountains looming

with calming familiarity.

The way the sky flowered

The way I used to live.

Shukria grew up in a small village in the mountains of Afghanistan, and always remembered it in her poems. After a year as our Forward Arts Foundation Student, she won a place at Goldsmiths to study politics.

England

In England: Poems from a School, the poetry of The Very Quiet Foreign Girls Poetry Group is brought together by poet and teacher Kate Clanchy.

No comments:

Post a Comment