Andy Bodle | The Guardian

This was from a couple of years ago:

How new words are born

English speakers already have over a million words at our disposal – so why are we adding 1,000 new ones a year to the lexicon? And how?

As dictionary publishers never tire of reminding us, our language is growing. Not content with the million or so words they already have at their disposal, English speakers are adding new ones at the rate of around 1,000 a year. Recent dictionary debutants include blog, grok, crowdfunding, hackathon, airball, e-marketing, sudoku, twerk and Brexit.

But these represent just a sliver of the tip of the iceberg. According to Global Language Monitor, around 5,400 new words are created every year; it’s only the 1,000 or so deemed to be in sufficiently widespread use that make it into print. Who invents these words, and how? What rules govern their formation? And what determines whether they catch on?

Shakespeare is often held up as a master neologist, because at least 500 words (including critic, swagger, lonely and hint) first appear in his works – but we have no way of knowing whether he personally invented them or was just transcribing things he’d picked up elsewhere.

It’s generally agreed that the most prolific minter of words was John Milton, who gave us 630 coinages, including lovelorn, fragrance and pandemonium. Geoffrey Chaucer (universe, approach), Ben Jonson (rant, petulant), John Donne (self-preservation, valediction) and Sir Thomas More (atonement, anticipate) lag behind. It should come as no great surprise that writers are behind many of our lexical innovations. But the fact is, we have no idea who to credit for most of our lexicon.

If our knowledge of the who is limited, we have a rather fuller understanding of the how. All new words are created by one of 13 mechanisms:

1 Derivation

The commonest method of creating a new word is to add a prefix or suffix to an existing one. Hence realisation (1610s), democratise (1798), detonator (1822), preteen (1926), hyperlink (1987) and monogamish (2011).

The commonest method of creating a new word is to add a prefix or suffix to an existing one. Hence realisation (1610s), democratise (1798), detonator (1822), preteen (1926), hyperlink (1987) and monogamish (2011).

2 Back formation

The inverse of the above: the creation of a new root word by the removal of a phantom affix. The noun sleaze, for example, was back-formed from “sleazy” in about 1967. A similar process brought about pea, liaise, enthuse, aggress and donate. Some linguists propose a separate category for lexicalisation, the turning of an affix into a word (ism, ology, teen), but it’s really just a type of back formation.

The inverse of the above: the creation of a new root word by the removal of a phantom affix. The noun sleaze, for example, was back-formed from “sleazy” in about 1967. A similar process brought about pea, liaise, enthuse, aggress and donate. Some linguists propose a separate category for lexicalisation, the turning of an affix into a word (ism, ology, teen), but it’s really just a type of back formation.

3 Compounding

The juxtaposition of two existing words. Typically, compound words begin life as separate entities, then get hitched with a hyphen, and eventually become a single unit. It’s mostly nouns that are formed this way (fiddlestick, claptrap, carbon dating, bailout), but words from other classes can be smooshed together too: into (preposition), nobody (pronoun), daydream (verb), awe-inspiring, environmentally friendly (adjectives).

The juxtaposition of two existing words. Typically, compound words begin life as separate entities, then get hitched with a hyphen, and eventually become a single unit. It’s mostly nouns that are formed this way (fiddlestick, claptrap, carbon dating, bailout), but words from other classes can be smooshed together too: into (preposition), nobody (pronoun), daydream (verb), awe-inspiring, environmentally friendly (adjectives).

4 Repurposing

Taking a word from one context and applying it to another. Thus the crane, meaning lifting machine, got its name from the long-necked bird, and the computer mouse was named after the long-tailed animal.

Taking a word from one context and applying it to another. Thus the crane, meaning lifting machine, got its name from the long-necked bird, and the computer mouse was named after the long-tailed animal.

5 Conversion

Taking a word from one word class and transplanting it to another. The word giantwas for a long time just a noun, meaning a creature of enormous size, until the early 15th century, when people began using it as an adjective. Thanks to social media, a similar fate has recently befallen friend, which can now serve as a verb as well as a noun (“Why didn’t you friend me?”).

Taking a word from one word class and transplanting it to another. The word giantwas for a long time just a noun, meaning a creature of enormous size, until the early 15th century, when people began using it as an adjective. Thanks to social media, a similar fate has recently befallen friend, which can now serve as a verb as well as a noun (“Why didn’t you friend me?”).

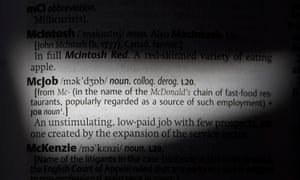

6 Eponyms

Words named after a person or place. You may recognise Alzheimer’s, atlas, cheddar, alsatian, diesel, sandwich, mentor, svengali, wellington and boycott as eponyms – but did you know that gun, dunce, bigot, bugger, cretin, currant, hooligan, marmalade, maudlin, maverick, panic, silhouette, syphilis, tawdry, doggerel, doily and sideburns are too? (The issue of whether, and for how long, to retain the capital letters on eponyms is a thorny one.)

Words named after a person or place. You may recognise Alzheimer’s, atlas, cheddar, alsatian, diesel, sandwich, mentor, svengali, wellington and boycott as eponyms – but did you know that gun, dunce, bigot, bugger, cretin, currant, hooligan, marmalade, maudlin, maverick, panic, silhouette, syphilis, tawdry, doggerel, doily and sideburns are too? (The issue of whether, and for how long, to retain the capital letters on eponyms is a thorny one.)

7 Abbreviations

An increasingly popular method. There are three main subtypes: clippings, acronyms and initialisms. Some words that you might not have known started out longer are pram (perambulator), taxi/cab (both from taximeter cabriolet), mob (mobile vulgus), goodbye (God be with you), berk (Berkshire Hunt), rifle (rifled pistol), canter (Canterbury gallop), curio (curiosity), van (caravan), sport (disport), wig (periwig), laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation), scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus), and trump (triumph. Although it’s worth noting that there’s another, unrelated sense of trump: to fabricate, as in “trumped-up charge”).

An increasingly popular method. There are three main subtypes: clippings, acronyms and initialisms. Some words that you might not have known started out longer are pram (perambulator), taxi/cab (both from taximeter cabriolet), mob (mobile vulgus), goodbye (God be with you), berk (Berkshire Hunt), rifle (rifled pistol), canter (Canterbury gallop), curio (curiosity), van (caravan), sport (disport), wig (periwig), laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation), scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus), and trump (triumph. Although it’s worth noting that there’s another, unrelated sense of trump: to fabricate, as in “trumped-up charge”).

8 Loanwords

Foreign speakers often complain that their language is being overrun with borrowings from English. But the fact is, English itself is a voracious word thief; linguist David Crystal reckons it’s half-inched words from at least 350 languages. Most words are borrowed from French, Latin and Greek; some of the more exotic provenances are Flemish (hunk), Romany (cushty), Portuguese (fetish), Nahuatl (tomato – via Spanish), Tahitian (tattoo), Russian (mammoth), Mayan (shark), Gaelic (slogan), Japanese (tycoon), West Turkic (horde), Walloon (rabbit) and Polynesian (taboo). Calques (flea market, brainwashing, loan word) are translations of borrowings.

Foreign speakers often complain that their language is being overrun with borrowings from English. But the fact is, English itself is a voracious word thief; linguist David Crystal reckons it’s half-inched words from at least 350 languages. Most words are borrowed from French, Latin and Greek; some of the more exotic provenances are Flemish (hunk), Romany (cushty), Portuguese (fetish), Nahuatl (tomato – via Spanish), Tahitian (tattoo), Russian (mammoth), Mayan (shark), Gaelic (slogan), Japanese (tycoon), West Turkic (horde), Walloon (rabbit) and Polynesian (taboo). Calques (flea market, brainwashing, loan word) are translations of borrowings.

9 Onomatopeia

The creation of a word by imitation of the sound it is supposed to make. Plop, ow, barf, cuckoo, bunch, bump and midge all originated this way.

The creation of a word by imitation of the sound it is supposed to make. Plop, ow, barf, cuckoo, bunch, bump and midge all originated this way.

10 Reduplication

The repetition, or near-repetition, of a word or sound. To this method we owe the likes of flip-flop, goody-goody, boo-boo, helter-skelter, picnic, claptrap, hanky-panky, hurly-burly, lovey-dovey, higgledy-piggledy, tom-tom, hip hop and cray-cray. (Willy-nilly, though, came to us via a contraction of “Will he, nill he”.)

The repetition, or near-repetition, of a word or sound. To this method we owe the likes of flip-flop, goody-goody, boo-boo, helter-skelter, picnic, claptrap, hanky-panky, hurly-burly, lovey-dovey, higgledy-piggledy, tom-tom, hip hop and cray-cray. (Willy-nilly, though, came to us via a contraction of “Will he, nill he”.)

11 Nonce words

Words pulled out of thin air, bearing little relation to any existing form. Confirmed examples are few and far between, but include quark (Murray Gell-Mann), bling (unknown) and fleek (Vine celebrity Kayla Newman).

Words pulled out of thin air, bearing little relation to any existing form. Confirmed examples are few and far between, but include quark (Murray Gell-Mann), bling (unknown) and fleek (Vine celebrity Kayla Newman).

12 Error

Misspellings, mishearings, mispronunciations and mistranscriptions rarely produce new words in their own right, but often lead to new forms in conjunction with other mechanisms. Scramble, for example, seems to have originated as a variant of scrabble; but over time, the two forms have taken on different meanings, so one word has now become two. Similarly, the words shit and science, thanks to a long sequence of shifts and errors, are both ultimately derived from the same root. And the now defunct word helpmeet, or helpmate, is the result of a Biblical boo-boo. In the King James version, the Latin adjutorium simile sibi was rendered as “an help meet for him” – that is, “a helper suitable for him”. Later editors, less familiar with the archaic sense of meet, took the phrase to be a word, and began hyphenating help-meet.

Misspellings, mishearings, mispronunciations and mistranscriptions rarely produce new words in their own right, but often lead to new forms in conjunction with other mechanisms. Scramble, for example, seems to have originated as a variant of scrabble; but over time, the two forms have taken on different meanings, so one word has now become two. Similarly, the words shit and science, thanks to a long sequence of shifts and errors, are both ultimately derived from the same root. And the now defunct word helpmeet, or helpmate, is the result of a Biblical boo-boo. In the King James version, the Latin adjutorium simile sibi was rendered as “an help meet for him” – that is, “a helper suitable for him”. Later editors, less familiar with the archaic sense of meet, took the phrase to be a word, and began hyphenating help-meet.

13 Portmanteaus

Compounding with a twist. Take one word, remove an arbitrary portion of it, then put in its place either a whole word, or a similarly clipped one. Thus were born sitcom, paratroops, internet, gazunder and sexting. (Note: some linguists call this process blending and reserve the term portmanteau for a particular subtype of blend. But since Lewis Carroll, who devised this sense of portmanteau, specifically defined it as having the broader meaning, I’m going to use the terms willy-nilly.)

Compounding with a twist. Take one word, remove an arbitrary portion of it, then put in its place either a whole word, or a similarly clipped one. Thus were born sitcom, paratroops, internet, gazunder and sexting. (Note: some linguists call this process blending and reserve the term portmanteau for a particular subtype of blend. But since Lewis Carroll, who devised this sense of portmanteau, specifically defined it as having the broader meaning, I’m going to use the terms willy-nilly.)

Some words came about via a combination of methods: yuppie is the result of initialism ((y)oung and (up)wardly mobile) plus derivation (+ -ie); berk is a clipped eponym (Berkshire hunt); cop, in the sense of police officer, is an abbreviation of a derivation (copper derives from the northern British dialect verb cop, meaning to catch); and snarl-up is a conversion (verb to noun) of a compound (snarl + up).

The popularity of the various methods has waxed and waned through the ages. For long periods (1100-1500 and 1650-1900), borrowings from French were in vogue. In the 19th century, loanwords from Indian languages (bangle, bungalow, cot, juggernaut, jungle, loot, shampoo, thug) were the cat’s pyjamas. There was even a brief onslaught from Dutch and Flemish.

In the 20th century, quite a few newbies were generated by derivation, using the -ie (and -y) suffix: talkies, freebie, foodie, hippy, roomie, rookie, roofie, Munchie, Smartie, Crunchie, Furby, scrunchie. Abbreviations, though, were the preferred MO, perhaps because of the necessity in wartime of delivering your message ASAP. The passion for initialisms seems to be wearing off, perhaps because things have got a little confusing; PC, for example, can now mean politically correct, police constable, per cent, personal computer, parsec, post cibum, peace corps, postcard, professional corporation or printed circuit.

But today, when it comes to word formation, there’s only one player in town: the portmanteau. Is this a bodacious development – or a disastrophe? I’ll get the debate rolling tomorrow.

Twitter: @AndyBodle

• This article was amended on 8 February 2016 to remove an incorrect reference to Oxford Dictionaries Online.

How new words are born | Media | The Guardian

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment